Dataset preprocessing with Guix scripts

Guix and Nix are both package managers that live within the purely functional package management paradigm that Eelco Dolstra pioneered. While they share the same idea and function in a very similar way, some differences make their day-to-day use quite different.

1. Licensing and reproducibility standpoint

Guix is a GNU project and respect the Free System Distribution Guidelines (FSDG). This means that no proprietary software (or even software that suggest you use proprietary software) is present in the official package channels. The Nix people care less about this, so you will find many proprietary packages in nixkpgs. Guix also upholds packaging guidelines similar to those of Debian: no vendoring is allowed, every compilation and runtime dependency of a package must come from another package, everything must be built from source. Again, the nix people don't care, so you will often find packages definitions that download prebuilt binaries when the compilation process is too complicated.

2. Package declaration language

Packages definitions in Nix are written in a special Domain specific language. Package definitions often embed many shell script snippets and make use of regular command line utilities. The Guix packages definitions (and also its command line utilities) are written in Guile Scheme, the GNU extension language.

(define-public hello

(package

(name "hello")

(version "2.12.1")

(source (origin

(method url-fetch)

(uri (string-append "mirror://gnu/hello/hello-" version

".tar.gz"))

(sha256

(base32

"086vqwk2wl8zfs47sq2xpjc9k066ilmb8z6dn0q6ymwjzlm196cd"))))

(build-system gnu-build-system)

(synopsis "Hello, GNU world: An example GNU package")

(description

"GNU Hello prints the message \"Hello, world!\" and then exits. It

serves as an example of standard GNU coding practices. As such, it supports

command-line arguments, multiple languages, and so on.")

(home-page "https://www.gnu.org/software/hello/")

(license gpl3+)))

stdenv.mkDerivation (finalAttrs: {

pname = "hello";

version = "2.12.1";

src = fetchurl {

url = "mirror://gnu/hello/hello-${finalAttrs.version}.tar.gz";

sha256 = "sha256-jZkUKv2SV28wsM18tCqNxoCZmLxdYH2Idh9RLibH2yA=";

};

doCheck = true;

passthru.tests = {

version = testers.testVersion { package = hello; };

invariant-under-noXlibs =

testers.testEqualDerivation

"hello must not be rebuilt when environment.noXlibs is set."

hello

(nixos { environment.noXlibs = true; }).pkgs.hello;

};

passthru.tests.run = callPackage ./test.nix { hello = finalAttrs.finalPackage; };

meta = with lib; {

description = "A program that produces a familiar, friendly greeting";

longDescription = ''

GNU Hello is a program that prints "Hello, world!" when you run it.

It is fully customizable.

'';

homepage = "https://www.gnu.org/software/hello/manual/";

changelog = "https://git.savannah.gnu.org/cgit/hello.git/plain/NEWS?h=v${finalAttrs.version}";

license = licenses.gpl3Plus;

maintainers = [ maintainers.eelco ];

mainProgram = "hello";

platforms = platforms.all;

};

})

For a regular user, using Nix would probably be a safer bet: it has a larger community, it has a less restrictive packaging policy and as a consequence, more proprietary software and device drivers will be available. However, Guix' use of a general purpose programming language for package definition lets us use it in very exotic ways! As tool for distributed data processing, for instance.

3. The problem

I want to develop a policy that will optimize HVAC system's energy consumption. One tool to develop such a policy (without having to waste a tons of money by testing it on real buildings) is the energy simulation software EnergyPlus. Usually, to run a simulation, we need a digital twin of the building we want to simulate, but the department of energy has a dataset of thousands of sample buildings that we can use. This is great, but these files are in an old format that energyplus used six versions ago and we need them to run them through a pipeline of six tiny programs to convert them to the new format. The task is pretty simple, we could probably write a simple shell script and be done with it.

However, there are thousands of different files, each file must go through 6 updates and each update takes 2-3 minutes (for some reason, they are very slow). Doing this would take too long, so I've decided to define the translation procedure using Guix: The purely functional model would ensure the result of each phase is memoized (so I can stop and resume the upgrade process when I want) and more importantly, its Offload facility would let me automatically distribute the work between all of my computers. Nix could defenitely be used for this task, but guix has some special facilities that will make our lives easier.

4. G expressions

Most of the languages in the LISP family are homoiconic. This means that the

syntax of the language can be manipulated as a regular data structure in the

language itself. This lets user write LISP programs that write LISP programs

which are sometimes very useful to abstract away syntactic (as opposed to

semantic) redundancies. One way of doing metaprogramming is quasiquote:

(define filename "/gnu/store...")

(define version "12.3.4")

(write

(quasiquote

(begin

(copy-file (unquote filename) "./")

(display (unquote version)) (newline))))

(begin (copy-file "/gnu/store..." "./") (display "12.3.4") (newline))

(quasiquote ...) (or its abbreviation `(...)) lets the user have a human

readable incomplete syntax tree (think of holes), then splice additional values

inside(using (unquote ...) or its abbreviation ,...) to generate a complete

piece of syntax. Quasiquote presents itself as a good way to generate code from

the package definition to be executed on the build side, but it has a problem:

because we can't control what the filename of a built package will be(this is a

consequence of the purely functional paradigm where the path of a built package

contains the hash of each of its dependencies), we have no way of knowing in

advance where some package binary will be located on the build side. Guix'

solution to this problem is G-expressions

(use-modules (guix gexp)

(gnu packages base))

(define some-constant "12345...")

(define exp

(gexp

(begin

(system* (string-append (ungexp hello) "/bin/hello"))

(with-output-to-file (ungexp output)

(lambda ()

(display "contents") (newline)

(display (ungexp some-constant)) (newline))))))

(write exp)

#<gexp (begin (system* (string-append #<gexp-input #<package hello@2.12.2 gnu/packages/base.scm:100 7f3b6fb94dc0>:out> "/bin/hello")) (with-output-to-file #<gexp-output out> (lambda () (display "contents") (newline) (display #<gexp-input "12345...":out>) (newline)))) 7f3b6f477390>

G-expressions (see [1]) are a way to construct pieces of syntax

that track the packages (and more generally, store items) on which their

execution depends. We use them in pretty much the same way we use quasiquote:

gexp (or #~ ) is like quasiquote and ungexp (or #$) is like unquote. Each

(ungexp <file-like-object>) inside a G expression will be transformed (on the

build side) into the store path of the given "file-like object". This lets us

write build side code without having to care about the location (and the build

order) of the dependencies.

5. File-like objects

How do we generate build side code (from the client side) acting on files that

don't exist yet and whose future location are unknown? File-like object. A

file-like object is something like a #<package>, an #<operating-system> or even

a #<origin> (which represents a file on the internet). We can use them together

with g-expressions to construct new file-like objects. We call these things

file-like objects because once we ask the guix daemon to build them, they will

become files (or directories) and will be placed within the store somewhere in

/gnu/store/. Our goal in the next section will be to construct a file-like

object containing the upgraded version of every idf file in our dataset.

6. Guix script

Here is what the code to do the multiple version updates look like.

#!/usr/bin/env -S guix build -f

!#

;; The shebang lets us execute it after having `chmod +x`-ed it.

(use-modules

(srfi srfi-1) ; List utilities

(guix gexp) ; For `gexp`, `local-file` and more.

(guix build utils) ; find-files

(terramorpha packages energyplus)) ; For the energyplus package itself

;; The whole chain of updates we need to go through

(define versions

'("9.5.0"

"9.6.0"

"22.1.0"

"22.2.0"

"23.1.0"

"23.2.0"

"24.1.0"))

update-version is the procedure that does most of the work. It takes a file-like

object, a source version, a target version and returns a g-expression that

builds the file for the target version.

;; A single update step.

(define* (update-version file #:key from to)

;; Turns a version name in 1.2.3 format into its 1-2-3 format.

(define (turn-version v)

(string-map (lambda (c) (if (eq? c #\.)

#\-

c))

v))

;; The idd file that describes the source version format

(define fromidd (string-append "V" (turn-version from) "-Energy+.idd"))

;; The idd file that describes the source version format

(define toidd (string-append "V" (turn-version to) "-Energy+.idd"))

#~(begin

;; On the build side, we first have to copy the format

;; specifiers for both versions in the working directory.

(copy-file (string-append #$energyplus "/PreProcess/IDFVersionUpdater/" #$fromidd)

#$fromidd)

(copy-file (string-append #$energyplus "/PreProcess/IDFVersionUpdater/" #$toidd)

#$toidd)

;; We also have to copy the file to convert in the working

;; directory.

(copy-file #$file "./file.idf")

;; Then, we run the appropriate binary (named like

;; Transition-V1.2.3-to-V1.2.4) on the input file

(system* (string-append

#$energyplus

"/PreProcess/IDFVersionUpdater/Transition-V"

#$(turn-version from)

"-to-V"

#$(turn-version to))

"./file.idf")

;; Finally, we copy the output file to the output path. Here,

;; #$output is a special variable pointing to the output path of

;; the current build procedure. It is similar to the $@ variable

;; in makefiles.

(copy-file "./file.idfnew"

#$output)))

This procedure returns a G-expression that track as dependencies the input file and energyplus. However, while a G-expression correctly tracks its dependencies, it is not considered a "file-like object" that can be built by the guix build daemon. We need to wrap the G-expression with the computed-file procedure for that.

;; update-all-the-way takes a file name (from the client side) and

;; returns a file like object that, when built, will give the fully

;; updated idf file.

(define (update-all-the-way filename)

(define name (basename filename))

;; if we had version 1, 2, and 3, transitions would contain

;; transition procedures of the form (1 -> 2, 2 -> 3) where each

;; arrow takes a file like object pointing to an idf file from a

;; version and returns a file like object pointing to an idf file

;; from the next version.

(define transitions (map (lambda (from to)

(lambda (file)

(computed-file (string-append (car (string-split name #\.)) "-" to ".idf")

(update-version file

#:from from

#:to to)

;; This argument is

;; important to allow

;; guix to execute it on

;; remote machines.

#:local-build? #f)))

(list-head versions (1- (length versions)))

(cdr versions)))

;; We apply each transition procedure one after the other.

(fold (lambda (updater file) (updater file))

;; local-file is important to take a file on the client

;; file-system and turn it into a file-like object that will

;; be accessible on the build side.

(local-file filename) transitions))

(define prof

(getenv "GUIX_LOAD_PROFILE"))

;; We list every idf file in our dataset.

(define all-idf-files

(find-files (string-append prof "/share/energyplus/buildings/") ".*\\.idf"))

;; For each of these files, we create a file-like object for their

;; upgraded version.

(define all-the-updated-files

(map update-all-the-way all-idf-files))

;; In the last file-like object, we assemble every artifact into a

;; common directory.

(define new-dataset

(computed-file

"energyplus-dataset-family-1a-24.1.0"

;; with-imported-modules lets us add scheme libraries to be made

;; available on the build side. (guix build utils) provides the

;; `install-file` procedure.

(with-imported-modules

'((guix build utils))

#~(begin

(use-modules (guix build utils))

(for-each

(lambda (filename)

(install-file filename (string-append #$output "/share/energyplus/buildings/"))))

'#$all-the-updated-files))

#:local-build? #f))

;; We end the program with an expression so that the file can be executed with `guix build -f`

new-dataset

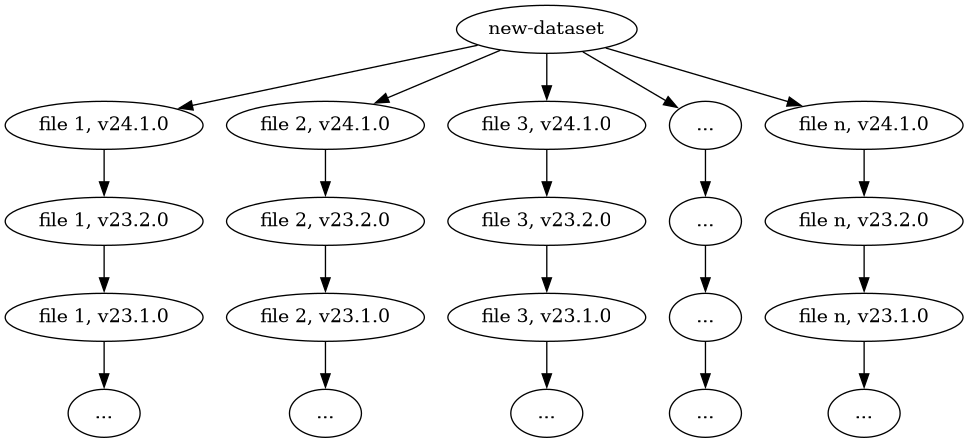

When the Guix build daemon tries to build the new-dataset object, it will

encounter 3000 independent jobs containing about 6 steps each.

7. Offloading

If you have set up offloading, the guix daemon will automatically dispatch each of these jobs on one of the build machines. If you have many build machines, this can make the whole process of translating the idf files a whole log quicker. While being used as a computing cluster coordinator (it automatically tracks build jobs and artifacts) is not what Guix was originally made for, the fact it uses a general purpose language like Scheme lets us extend it to weird use cases. The same idea was also developped further by people from the scientific computing world which gave birth to the Guix Workflow Language.